NIDA Points of Interest

About NIDA

Advancing the science on drug use and addiction

Director's Page

Nora D. Volkow, M.D., became Director of NIDA in May 2003.

Grants & Funding

Research grants, contracts, and supplements related to drug use and addiction.

NIDAMED: Clinical Resources

Substance use screening tools, guidelines, and other resources.

Research & Training

Programs to support research training from high school through tenure.

NIDA Research Programs & Activities

Learn about NIDA-supported research and cross-agency research activities on drug use and addiction.

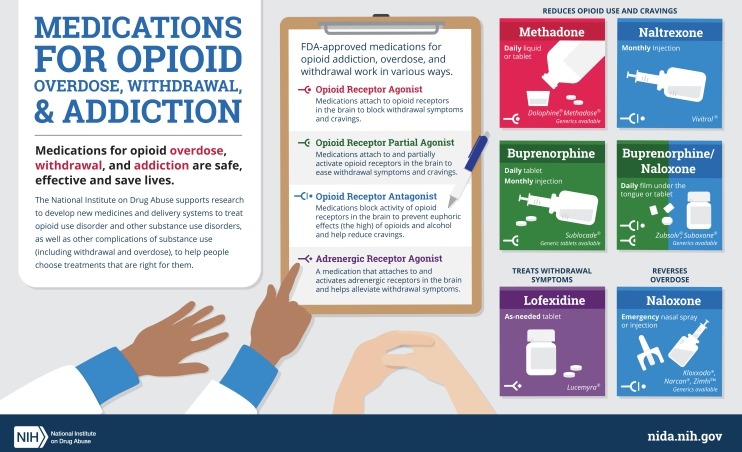

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

Medications for opioid use disorder are safe, effective, and save lives. This NIDA-produced video takes a closer look at these medications and how they work.

Explore Topics in Substance Use and Addiction Science

Upcoming Meetings/Events

National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse: Open Session – September 2025

|

Neuroscience Center, 6001 Executive Blvd