This study reported:

- About 1 in 20 patients treated for a nonfatal opioid overdose in an emergency department (ED) died within 1 year of their visit, many within 2 days.

- Two-thirds of these deaths were directly attributed to subsequent opioid-related overdoses.

- Immediate treatment for substance use disorder in the ED that continues after discharge is needed to reduce opioid-related deaths.

Every year, emergency departments (EDs) across the country treat thousands of patients for nonfatal opioid overdoses, and this number continues to rise. These patients are typically observed in the ED and then discharged with information about finding outpatient treatment. But what happens to these patients after they leave the ED? A recent study showed that many of these people died within a year, often within the first couple of days after discharge. “Our research demonstrated that about 1 in 20 people who presented to the ED with an overdose and were discharged were dead within a year,” explains Dr. Scott G. Weiner, the study’s first author and a NIDA-funded investigator. “That’s a startlingly high number and perhaps shocking enough to make it clear that simply providing a paper list of detox facilities to these patients at discharge, as we have done for the past several decades, is not sufficient.”

Dr. Weiner and his colleagues from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston partnered with the Massachusetts Department of Health to determine the number of deaths that occurred among 11,557 patients who were treated for a nonfatal opioid overdose and then discharged from Massachusetts EDs. They linked state-wide data on patients who had been treated and discharged from an ED for an opioid overdose between July 2011 and September 2015 with state death records up to September 2016. This allowed them to determine the number of deaths that occurred between 1 day and 1 year after the initial ED visit.

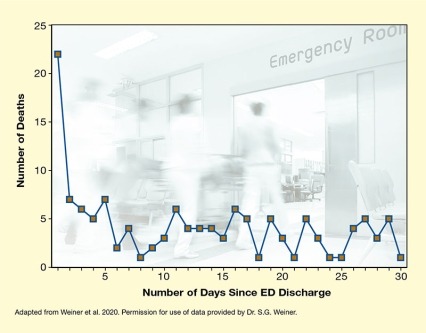

Of patients who died within the first month after receiving treatment in the ED for a nonfatal opioid overdose (n=130), about one in five died within the first 2 days. See full text description at end of article.

Dr. Weiner and colleagues found that of these patients, 635 (5.5 percent) died within 1 year of their ED visit, including 130 who died within the first 30 days and 29 who died within the first 2 days after discharge. In other words, 1 in 5 patients who died within a year did so within the first month, and particularly within the first 2 days (1 in 25) (see Figure). About two-thirds of the deaths (428 patients) resulted directly from a subsequent opioid-related overdose. Those who died were relatively young (median age 39 years), and almost one-quarter died at a residence, suggesting that they may have died before help arrived.

Because the study was limited to EDs in Massachusetts, the results may not be generalizable to other areas. In addition, the data did not include patients who either received treatment for overdose outside of Massachusetts but died in the state, or who had received treatment in a Massachusetts ED but died in another state. Nevertheless, the extremely high mortality rate among these patients, particularly shortly after the ED visit, supports the need for immediate substance use disorder treatment in the ED that continues through discharge and follow-up. “Knowing the high mortality rate of these patients makes the case for EDs to provide buprenorphine to appropriate patients and for health systems to create rapid-access ‘bridge clinics’ for patients who are in desperate need of help,” says Dr. Weiner.

Bridge clinics, which have been established as part of a harm-reduction model in many health systems, including Massachusetts, will see patients on a walk-in basis, regardless of insurance status or current drug use. Dr. Weiner explains, “The model works: About 80 percent of our patients are actively engaged in treatment. Our emergency physicians now know that their buprenorphine prescription is an important link in the survival chain to then get the patient to the bridge clinic.” He adds, “In future studies, I would want to determine how the 1-year mortality rates vary for patients who receive care through these novel approaches to treatment as opposed to the old way of simply providing a ‘detox list’.”

NIDA offers evidence-based resources and videos for emergency department clinicians based on seminal research done at Yale University on how to transition opioid use disorder patients to buprenorphine treatment.

This study was supported by NIDA grant DA044167.

- Text description of Figure

-

The image shows the number of deaths occurring within 30 days among patients treated for opioid overdose and discharged from emergency departments (EDs), overlaid on a background image showing a scene from an emergency room. The horizontal x-axis shows the number of days since ED discharge from 1 to 30; the vertical y-axis shows the number of deaths from 0 to 25. The numbers of deaths were 22 on Day 1, 7 on Day 2, 6 on Day 3, 5 on Day 4, 7 on Day 5, 2 on Day 6, 4 on Day 7, 1 on Day 8, 2 on Day 9, 3 on Day 10, 6 on Day 11, 4 each on Days 12 to 14, 3 on Day 15, 6 on Day 16, 5 on Day 17, 1 on Day 18, 5 on Day 19, 3 on Day 20, 1 on Day 21, 5 on Day 22, 3 on Day 23, 1 each on Days 24 and 25, 4 on Day 26, 5 on Day 27, 3 on Day 28, 5 on Day 29, and 1 on Day 30.

Source:

- Weiner, S.G., Baker, O., Bernson, D., Schuur, J.D. One-year mortality of patients after emergency department treatment for nonfatal opioid overdose. Ann Emerg Med 2020;5(1):13-17, 2020.